About Gabrielle Zevin

Zevin’s Career began with her debut novel Margarettown, published in 2005, chosen for the Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers Program and praised in a starred review by Kirkus Reviews as a droll piece filled with romantic whimsy and unexpected resonance, later reaching the James Tiptree Jr. Award longlisted circle. She kept expanding her craft through work for NPR’s All Things Considered, the New York Times Book Review, and the screenplay Conversations with Other Women, which earned her a nominated spot for an Independent Spirit Award for Best First Screenplay with Hans Canosa, Helena Bonham Carter, and Aaron Eckhart, while her young adult successes Elsewhere, an American Library Association Notable Children’s Book translated into 25 languages, and Memoirs of a Teenage Amnesiac, adapted in 2007 into the Japanese movie Dareka ga Watashi ni Kiss wo Shita starring top teen idol Maki Horikita showed a writer whose selection, screenplay, and storytelling always reached beyond borders.

Her Novels for adults grew this reach, beginning with A. J. Fikry, which debuted in 2014, climbed the New York Times Best Seller List and the National Indie Best Seller List, became an international bestseller, and was translated into thirty languages before shooting commenced in 2021 for the feature film adaptation starring Kunal Nayyar, Lucy Hale, Christina Hendricks, Scott Foley, and David Arquette. In 2017, Young Jane Young earned critical acclaim, even linked to the Monica Lewinsky scandal and her magnificent TED talk, while Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, her fifth novel, released in 2022, won the Goodreads Choice Award for Best Fiction, reached seventy-six on the 100 Best Books of the 21st Century, and continued her rise as a Best Seller, with her own screenplay adaptation showing how naturally her stories move, travel, and remain deeply human.

PLOT of tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow

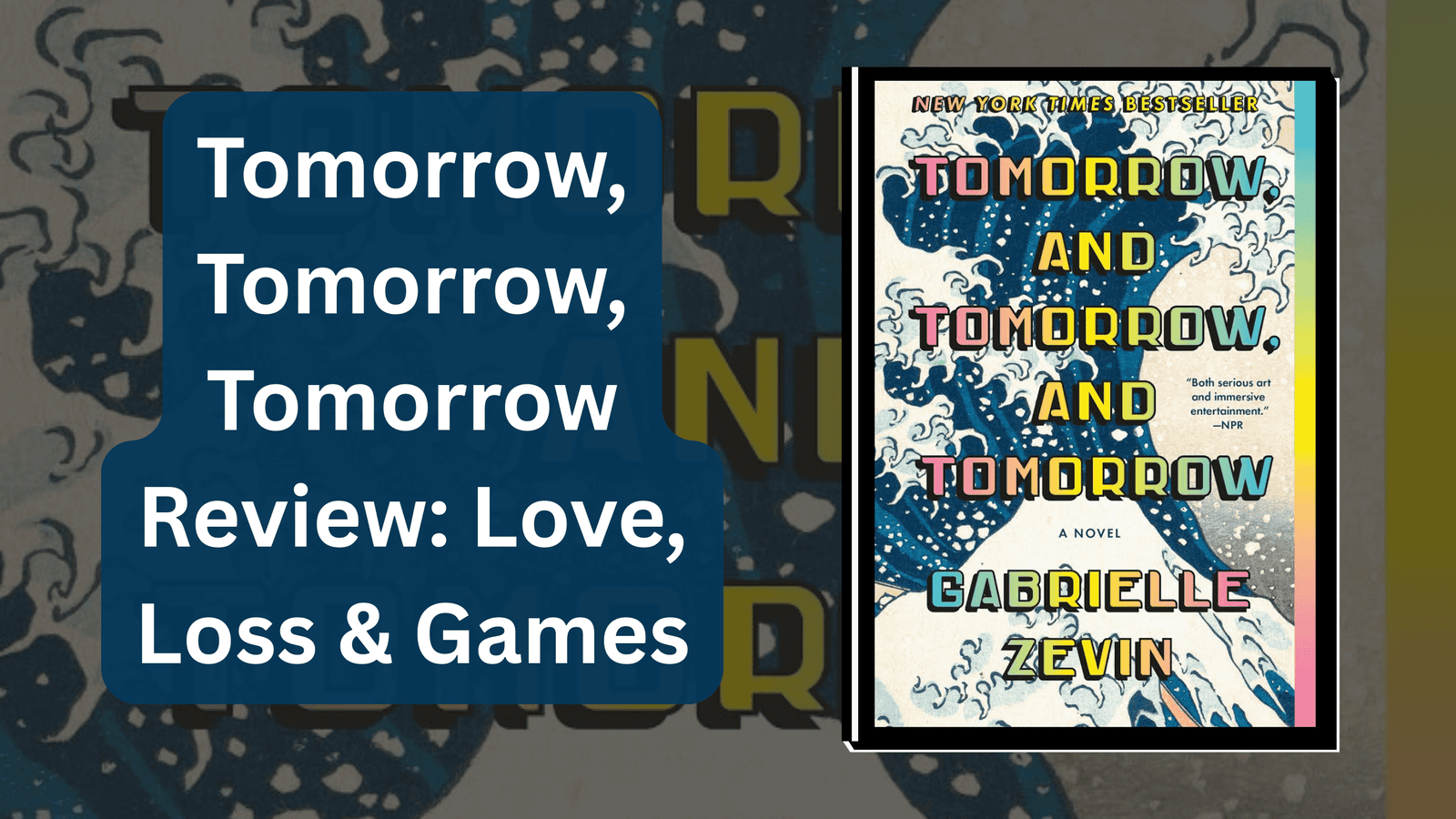

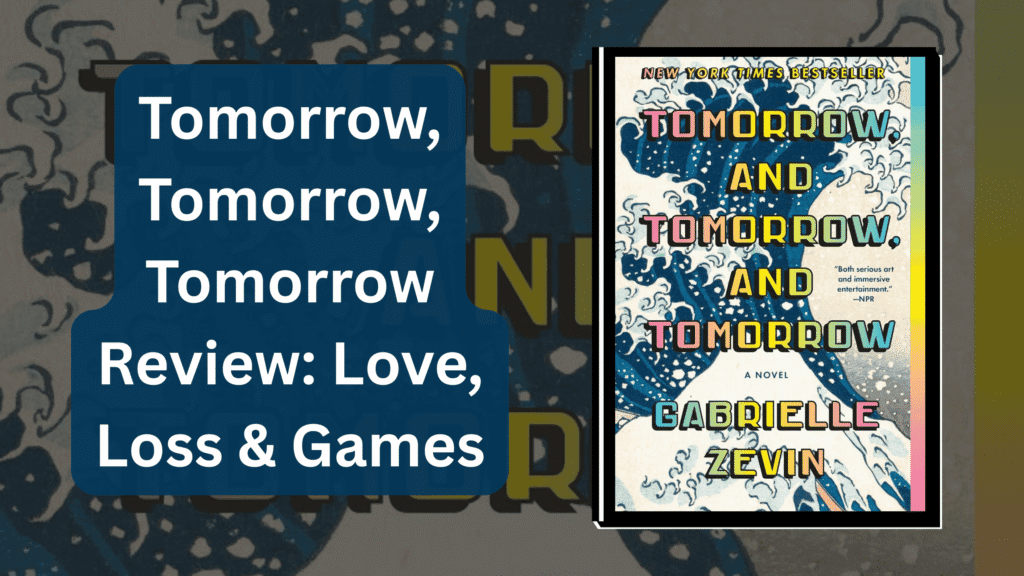

I admit, my journey to Gabrielle Zevin’s novel, Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, was full of apprehension. It was not because the book doesn’t seem promisingly in fact, the first chapter, and particularly the first half of the first chapter, is wonderfully well written and a joy to read. I initially felt the subject matter was not my cup of tea. I’ve spent enough time in the world of tech and video game industry to be wary of fictional takes. But, when major literary publications started listing it repeatedly as one of the best books of 2022, I was finally convinced to give the book a chance.

My initial reaction to the overall structure, though, was that it felt like taking a bunch of stuff I happen to like and put it in a blender it doesn’t come out a unified whole. It felt, at times, like a patchwork of little substance, a best-selling mediocre effort, or perhaps even a self-aware tagline. There were parts here and there, certain imaginative landscapes and certain descriptions mostly, that were excellently written. But the novel as a whole sometimes felt like eating at a fast food restaurant—the things look enticing at first, but there’s no there there and you end up leaving hungry.

The Anatomy of Creative Partnership: Sam and Sadie’s Story

This is the story of Sam and Sadie. It’s not a romance, but it is about love. It begins when Sam catches sight of Sadie at a crowded train station one winter morning, and he is catapulted back to the brief time they spent playing together as children. That unique spark is instantly reignited.

Zevin’s tenth novel charted the story of Sadie Green and Samson (Sam) Masur. They first met in their early teenage years in most unusual circumstances and places: Sadie was in the hospital helping to nurse her sister Alice who was undergoing treatment for cancer. Meanwhile, Sam was recovering from a foot injury after a horrific car accident that killed his mother, Anna Lee. The trauma was so great that Sam had not spoken a word to anyone. Instead, he channeled his attention and energies into playing Super Mario Bros in the children’s ward recreation room. Both Sadie and Sam shared an interest in gaming. A casual meeting at the recreation room led to a friendship built around their love for video games.

The novel alternates between flashbacks that flesh out that backstory and the main narrative that follows them creating computer games and founding a gaming company. The novel is a thoroughly entertaining and engaging tale of friendship that explores rivalry, fame, creativity, betrayal, and tragedy, set across both perfect worlds and imperfect ones. Ultimately, our need to connect: to be loved and to love. Sam and Sadie are university students when they reconnect in 1996: Sam is studying Mathematics at Harvard University, and Sadie is pursuing computer science at MIT. They rebuilt what was once stalled. As they say, some things never change: Sam and Sadie were still both passionate about video games. Sadie has a knack for designing games while Sam was gifted at creating mazes and puzzles. Sam convinced Sadie to collaborate on designing a game. They shared a mutual respect for each other’s works and creative process. They also understood and respected how each worked.

Their business-cum-friendship deal led to the birth of Unfair Games, supported by Sam’s wealthy and generous roommate, Marx Watanabe, who becomes their producer. The first product of their collaboration was Ichigo. It was an overnight sensation, a blockbuster that made all the challenges they had to go through worthwhile. Barely in their mid-twenties, Sam and Sadie, and by extension, Marx, were rich and successful.

The Characters and Themes: A Look at the ‘Woke’ World

I found the depiction of Sam on the ace spectrum and the positive depiction of race with Jewish, Korean, Japanese cultures creating a real synthesis and energy to be refreshing. Sam felt authentically Korean, and his Korean background mixed with Sadie’s Jewish heritage and Marks’ Japanese upbringing to create something new, energised, and creative. Sam certainly had his trauma from the accident, and his impoverished upbringing and debt conflicts with Sadie’s relative affluence. He seemed somewhere on the ace spectrum and is described within the novel by other characters as somewhere on the autistic spectrum.

However, the characters include and I kid you not: a Jewish Korean only child that is a talented math nerd who goes to an Ivy League college (Sam); a Jewish princess video game designer (Sadie); a gay video game designer couple; an ex-Mormon video game designer couple; and even a manic dream pixie girl that composes music naked to feel closer to her instrument. It often felt like the book was trying hard to be woke, breaking into a sweat, and not really addressing or representing the historical era it is set in or the video game industry with any depth.

As a woman who has worked in a male dominated field, my personal expertise made Sadie’s experience utterly, utterly unrepresentative of the challenges women face. There is lip service in a few scenes where Sam get the credit for her work, but Zevin was clearly not really interested in tackling the experience of always being the only woman in a room full of people who don’t believe you should be there. Sadie had to contend with latent sexism both in the workplace and beyond it. Because of this, she always had to play second fiddle to Sam. She was the better game designer but she had to fold to the pressures and demands of the industry and of her male peers. Sam received the praises and the accolades, and Sadie had to watch on the stands.

The novel introduces spicy characters and themes as if they were thrown in every time Zevin felt that she might be losing her reader. The book skirts all kinds of interesting themes sexism, racism, abuse, trauma, disability, the immigrant experience, financial and class disparities, creative ruts but tackles non of them. They all go whoosh by, leaving no mark, placed there just as if they were chores on Zevin’s list.

Issues with Character and Narrative Flow

My main points of criticism revolve around the central figures. The childish, selfish, self involved, self destructive Sadie and Sam, the main characters, don’t change at all during the novel. They behave as adults exactly as they behaved as children. Not only is this incredibly boring, it’s also bewildering that this was termed a “coming of age” novel. They don’t grow up, so what exactly is the plot here?

The plot is just time passing with incidents and character behaviours and interactions that are unearned and unwarranted. The only reason things seem to be “happening” is because Zevin feels like she might be losing her reader. This happening (in brackets because the events show little to no lasting effect on the main characters’ behaviour or choices beyond the superficial) often feels like narrative manipulation. The worst of these “happenings” is the killing off of a likeable character. Once he’s killed, you realize the only reason he was there and was likeable was so that Zevin can kill him off. It’s unwarranted, unearned, and insulting to the intelligence of the reader. Then you realize the involvement with Sadie and Sam was so outlandish in the first place that Zevin felt the need to justify it several times in the novel.

Also, the second half of the novel seemed a little… meandering? The Plotting could have been tauter. This narrative loosening is a problem; Tragedy does strike and was movingly done but the narrative somehow unravels, and Sam’s actions towards the end, which others praised as romantic, felt more than a little creepy to me.

Oh, and the use of Shakespeare (and “The Iliad”) is utterly unearned and jarring. I have no idea how Zevin or her publisher had the gall to name the book after such a masterpiece of a speech.

I strongly recommend that you spend your reading elsewhere. The bits and pieces worth reading aren’t worth the bits and pieces not.

continue reading

- Tuesdays with Morrie Review: Lessons on Life & Death

- VIOLENCE OF ACTION Review: Adrenaline-Fueled Thriller

- The Outsider Who Broke the Liars’ System

- Tom Lake Book Review by Ann Patchett || A Ponderous Look at Past Love, Secrets, and Mother-Daughter Relationships

- This Is Happiness Book Review: Niall Williams’ Beautiful Novel About Rain, Love, and Rural Ireland

- Is The Underground Railroad Too Painful?

6 thoughts on “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow Review: Love, Loss & Games”