about Colson Whitehead

Colson Whitehead is one of the most distinguished contemporary American novelists, having achieved the rare distinction of winning the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for two consecutive novels: The Underground Railroad (2017) and The Nickel Boys (2020). Born in 1969 and raised in Manhattan, Whitehead began his career after graduating from Harvard by writing reviews of television, books, and music for The Village Voice. His debut novel, The Intuitionist (1999), established his unique voice, blending elements of the noir detective genre and speculative fiction with a penetrating focus on race and institutionalized racism, setting the stage for a career defined by innovation and a willingness to explore a vast range of genres. He has also been recognized with numerous other top honors, including a MacArthur Fellowship and the National Book Award.

Whitehead’s writing is characterized by its genre fluidity and a thematic concentration on the American experience, particularly the history and reality of racial identity, memory, and trauma. His works span an impressive literary landscape, moving from the postmodernist allegory of elevator inspectors in The Intuitionist and the post-apocalyptic zombie horror of Zone One, to the historical fiction that utilizes magical realism to expose deeper truths. The Underground Railroad reimagines the historical escape network as a literal subterranean train system, while The Nickel Boys is a searing indictment of systemic abuse at a Jim Crow-era reform school based on a true story. He has also explored the crime noir genre with his recent Harlem Trilogy, confirming his reputation as a writer who constantly reinvents his narrative approach to critique American tradition and culture.

PLOT of the underground railroad

The Underground Railroad begins not with the protagonist, Cora, but with her grandmother, Ajarry, establishing the central theme of enduring generational trauma and resilience. Ajarry is kidnapped from her West African homeland and survives the horrors of the Middle Passage. Sold multiple times, she eventually lands on the infamous Randall cotton plantation in Georgia, where she will spend the rest of her life. Despite the unbearable conditions, the loss of children, and the constant threat of violence, Ajarry embodies an unbreakable determination, acquiring a small plot of land a tiny symbol of ownership and hope which she passes down to her daughter, Mabel. Ajarry’s life is a testament to survival, providing the foundation for Cora’s own fierce spirit.

Cora’s life on the Randall plantation is marked by a profound sense of abandonment. Her mother, Mabel, is the only enslaved person ever known to have successfully escaped the plantation, vanishing completely when Cora was just ten. For Cora, Mabel’s disappearance creates a complex, damaging legacy: while Mabel becomes a mythical figure of freedom to the other enslaved people and a source of shame for the white masters, she leaves Cora an isolated “stray” among her peers. This isolation and the necessity of self-defense forge Cora into a solitary, pragmatic, and unyielding young woman. She fiercely defends her inherited garden plot, symbolizing her last connection to family and self-possession, against all contenders.

The daily life on Randall is governed by the two brothers who own it: the relatively passive James and the sadistically cruel Terrance. The plantation’s horrors are laid bare during a gathering for “Jockey’s birthday.” When a young boy named Chester accidentally spills wine on Terrance, he unleashes a savage beating. In a spontaneous act of bravery, Cora intervenes, shielding the boy with her own body, which results in her being brutally whipped and punished. This act of defiance against her master, coupled with the escalating brutality after James’s death leaves Terrance in full control, convinces Cora that running is the only remaining path.

Cora’s decision to run is solidified by the agonizing, public, three-day torture and death of the recaptured runaway, Big Anthony, which Terrance uses to terrify the other enslaved people. This spectacle demonstrates that staying means slow, inevitable death or worse, while running at least offers the chance for swift death or freedom. Caesar, a fellow enslaved man from Virginia with a more worldly perspective, approaches Cora with a plan, recognizing the defiant fire in her. Though initially hesitant, Cora agrees to join him, seeing no other option to preserve her dignity or her life.

Under the cloak of darkness, Cora and Caesar slip away. Their meticulous plans are immediately complicated when they are unexpectedly followed by Lovey, a young, simple friend of Cora’s who begs to join them. This small act of naive hope proves disastrous. Before they can get far, the trio is intercepted by a group of white hog hunters. The hunters quickly seize Lovey, but Cora and Caesar fight back desperately, their escape transforming into a violent struggle for survival against the heavily armed white men.

During the ensuing melee, Cora is tackled by a teenage white boy. Terrified and cornered, she grabs a rock and strikes him repeatedly in the head, knocking him unconscious and leaving him for dead. This act the killing of a white person seals their fate. Lovey is captured and taken back to Randall, where she will face unimaginable punishment. Cora and Caesar flee, their fear now mixed with the chilling knowledge that they are no longer just runaways but murderers hunted by the full, vengeful force of the law, setting the stage for the relentless pursuit of the antagonist, Ridgeway.

Following their escape, Cora and Caesar are guided by a white abolitionist shopkeeper to the first true stop on the Underground Railroad, which, in the novel, is a literal subterranean train system complete with tracks, engines, and stations. They descend into the earth, stunned by the physical reality of the railway a powerful piece of magical realism that symbolizes the immense effort and collective memory required to forge a path to freedom. They board a train and travel to South Carolina, their first temporary refuge.

South Carolina appears, at first, to be a modern-day utopia. They are met by the friendly station agent, Sam, and given comfortable, communal housing, jobs, and forged papers with new identities. The state has embarked on a radical experiment in “racial uplift,” seemingly offering Black residents an advanced, progressive life far removed from the brutalities of the plantation. Cora finds employment first as a maid and then in a staged, living museum exhibit meant to educate white visitors about the mild horrors of slavery a deeply unsettling parody of their real-life trauma.

This comfortable facade slowly crumbles as Cora becomes suspicious of the state’s medical practices. She discovers that the government-sponsored health initiatives are a cover for a heinous eugenics program, including the forced sterilization of Black women and conducting deadly, unethical experiments on Black men, such as tracking the progression of syphilis. South Carolina, despite its modern gloss, merely substitutes outright slavery with a calculated, institutionalized form of control and genocide a chilling foreshadowing of historical atrocities like the Tuskegee experiment.

The danger becomes acute when the legendary and terrifying slave catcher, Arnold Ridgeway, arrives in town, tracked by his odd, preternaturally silent Black companion, Homer (a young boy whom Ridgeway “freed” only to keep by his side). Ridgeway, obsessed with capturing Cora to avenge his sole professional failure Mabel’s escape quickly closes in. Ridgeway’s motivation is intensely personal and philosophical: he seeks to reaffirm the inherent, divinely ordered rightness of the “American imperative,” which he defines as the white man’s right to dominion and profit, a system Mabel’s freedom invalidated.

Warned by Sam that their identities have been compromised and a mob is approaching, Cora descends back into the station tunnel. In the ensuing chaos, Sam’s house is attacked and burned. Cora waits for Caesar, but he is apprehended by Ridgeway’s men and later brutally murdered by a mob. Cora is forced to flee alone, narrowly escaping on a passing train after days spent hiding in the dark, abandoned station. Her time in South Carolina ends in devastating loss, reinforcing the novel’s tragic message that the search for freedom often requires unimaginable sacrifices and that no place in America is truly safe for Black life.

Cora’s next stop is a closed-down station in North Carolina, a state that has taken its own extreme measures: it has outlawed all Black people entirely, whether enslaved or free. The few Black residents who remain are forced into hiding or executed. The state operates on an absolute, violent form of white supremacy, publicly lynching any Black person or abolitionist sympathizer who is caught. The result is the gruesome “Freedom Trail,” a visible path lined with the decomposing bodies of executed Black people, serving as a brutal, terrifying warning to the outside world of the state’s radical racism.

Cora is reluctantly taken in by Martin Wells, a nervous and reluctant white station agent and failed abolitionist who lives in paralyzing fear, and his deeply resentful wife, Ethel. Martin hides Cora in a tiny crawl space in their attic for several agonizing months. Isolated and starved of human contact, Cora’s only window to the outside world is a small hole through which she can see the horrifying Friday night festivals, the town gathering to watch the public spectacle of Black executions. She witnesses firsthand the cold, calculated terror that North Carolina uses to maintain its purity.

During her time in the attic, Cora becomes gravely ill with a fever. Martin and Ethel, at great personal risk, bring her downstairs to nurse her back to health. Ethel, a devout but self-deluding woman who once harbored dreams of missionary work in Africa, attempts to use this time to redeem her conscience by reading scripture to Cora. However, their desperate secrecy is compromised when their maid grows suspicious and reports them to the authorities, proving that even tentative acts of kindness carry immense risk.

Ridgeway, still obsessively pursuing Cora across state lines, arrives during one of the town’s execution festivals. He captures Cora, saving her from the immediate threat of the mob only to chain her up as his property. The mob, enraged by the Wells’ betrayal, drags Martin and Ethel out and brutally executes them—the terrified abolitionist couple meeting the same fate as the people they tried, however weakly, to help. Cora watches helplessly as the final vestiges of her sanctuary burn, a scene that deeply underscores the danger of challenging the systemic racial order.

Chained and completely broken, Cora is forced to travel with Ridgeway, Homer, and the violent slave catcher Boseman as they detour through Tennessee to return another fugitive. The journey through the charred, desolate landscape of former Cherokee land is a brutal march through the American wasteland, a land made infertile by forced displacement and historical violence. Ridgeway lectures Cora constantly, revealing his twisted philosophy of the “American imperative,” arguing that the only moral order is the one that asserts power, and that Cora’s pursuit is essential to maintaining that order.

The journey with Ridgeway is a low point for Cora, marking a return to bondage. She is tortured physically and psychologically, forced to listen to Ridgeway’s self-justifying narratives about white supremacy. The party picks up another captured runaway, Jasper, who silently sings hymns until his death, serving as a constant reminder of the spiritual cost of slavery. Ridgeway even kills Boseman for his insolence, demonstrating the slave catcher’s willingness to dispense violence arbitrarily, even against his own men.

While stopped in Tennessee, Cora is rescued during a daring raid led by Royal, a charismatic, free born Black man and an active conductor on the Underground Railroad. Royal and his team ambush Ridgeway’s party, severely wounding Ridgeway and forcing his retreat. Royal then escorts Cora to the next stage of her journey, bringing her to a thriving, hopeful community that promises the genuine possibility of freedom, offering the first true companionship Cora has experienced since leaving Georgia.

Cora and Royal travel to Valentine Farm in Indiana, a large, well-organized cooperative run by free Black people and escaped fugitives. Here, Cora finds a measure of stability she has never known. She works the land, attends a school where she learns to read properly, and begins a tender, romantic relationship with Royal. The farm is an intentional community a microcosm of a truly free Black Americ that prioritizes education, self-governance, and collective prosperity, offering Cora a glimpse of genuine peace and belonging that finally starts to heal her deep-seated isolation.

However, even this haven is fragile. The farm is constantly threatened by racist white neighbors and a faction within the farm who fear the escaped fugitives will jeopardize their own safety. The community’s sense of security is violently shattered when a white mob attacks the farm during a lecture by a traveling Black abolitionist orator. The massacre is swift and brutal, destroying the farm and killing many residents, including Royal, who dies in Cora’s arms, forcing her to confront yet another profound loss and the impossibility of any permanent, secure Black life in America.

In the chaotic aftermath of the massacre, Cora is once again captured by Ridgeway and Homer. Ridgeway, nearing the end of his obsessive hunt, forces Cora to take him to a nearby, disused “ghost station.” During this final encounter, the true fate of Mabel is revealed: she never reached freedom, having died from a snake bite in the swamp while trying to return to Cora. This revelation offers Cora a painful sense of closure, replacing rage with profound sorrow and understanding.

When they reach the tracks, Cora makes her final stand. She shoves Ridgeway down the station steps, mortally wounding him. Leaving the dying slave catcher to reflect on his twisted philosophy with Homer taking notes, Cora boards a small handcar on the tracks. She pumps the handcar through the deep, unknown tunnel, her future stretching before her as an uncertain void a journey powered solely by her own will and labor, symbolizing her final, self-directed act of liberation.

After traveling for an indeterminate distance in the ghost tunnel, Cora emerges into the daylight in an unknown territory. She eventually encounters a procession of covered wagons driven by Black people heading West. The last wagon is driven by an older Black man, Ollie, who offers her a ride, food, and a blanket. Cora steps onto the wagon, not knowing where she is going or what awaits her, but finally moving toward a freedom she has fought and bled for. The novel concludes on this ambiguous note, confirming Cora’s relentless journey but leaving the final destination of her freedom unwritten, a testament to the ongoing and uncertain struggle for Black autonomy.

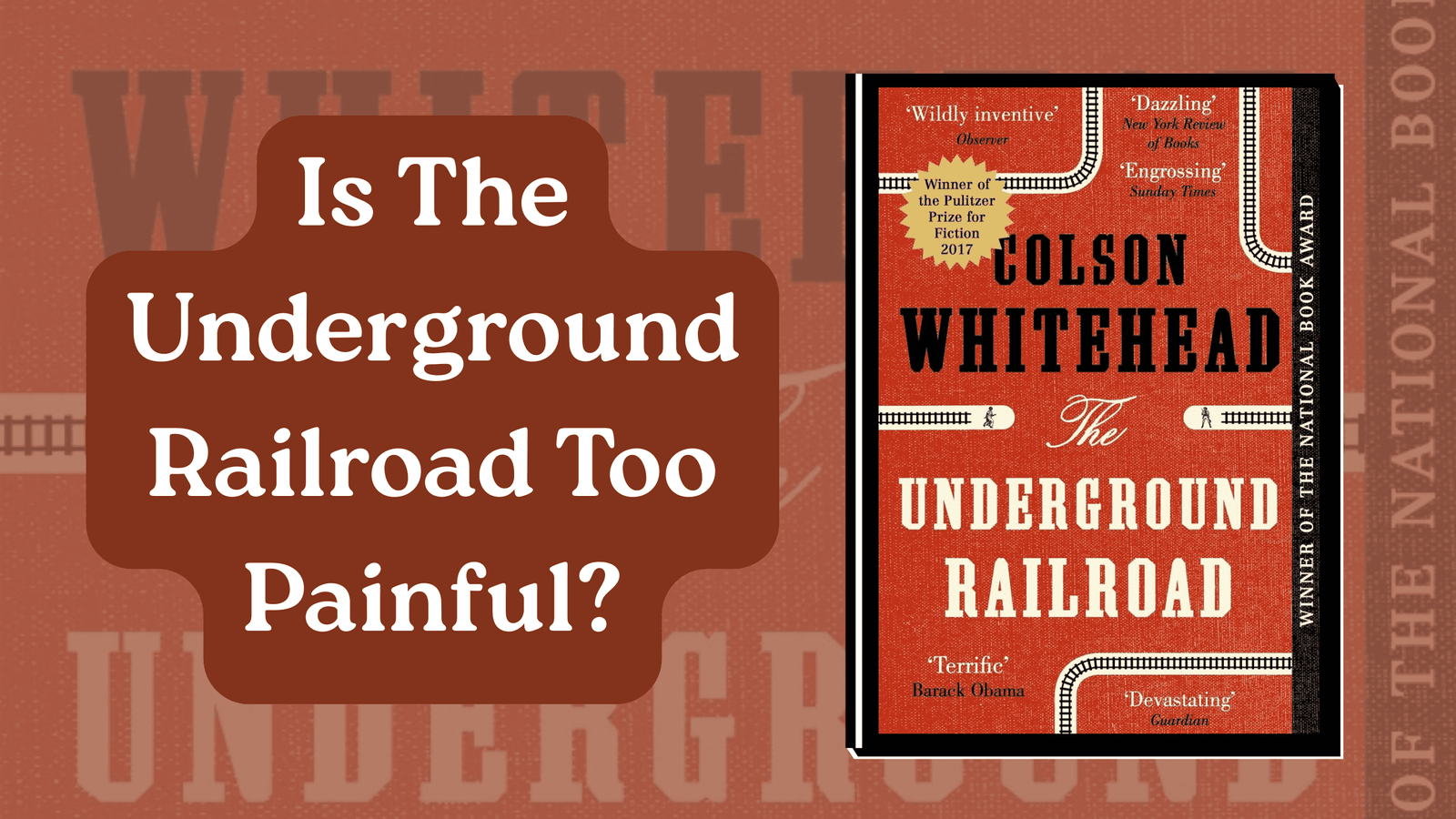

4 thoughts on “Is The Underground Railroad Too Painful?”